Developed: 2014; Last updated: Unknown.

I bought my first kayak, right in the middle of a balmy June. It was great, the weather was perfect, and I spent the better part of a week out on the water every afternoon.

August faded into September, the sun started setting earlier and earlier, and as soon as the fall winds started to blow, my boat ¬ and me with it – was out of the water for the winter. Little did I know that I was missing the best part. The serious paddling season doesn’t wait for the weather; it comes down from the mountains with the spring thaw and floods the rivers with icy-cold water. By the time the 90-degree days come along, most paddlers are packing up and heading for home, ready to wait for the next batch of serious water come winter.

I soon discovered that, if I wanted to really enjoy the best paddling conditions, I’d needed to be ready to hit the water anytime, regard less of the weather. Needed to be ready for the “snow on the ground,” “icicles in the beard” days that keep most folks inside. And to do that, I needed to learn how to dress for the cold.

There are three rules to remember when dressing for cold weather:

- No cotton. It soaks up water and holds it against your skin, leaving it worthless as an insulator and heavy as a layer. A worthless, worthless fabric in the water.

- Layers help trap heat and fend off water. Remember “wick, warmth, and weather” as you arrange your layers ¬ light wicking fabrics first, then warm insulating sweaters or fleeces, and finally an waterproof outer layer to protect you from the elements.

- No cotton; seriously.

Wetsuit or drysuit?

The Farmer John, or overall-type, wetsuit is a paddling classic. Timeless as a hand-me-down tuxedo, it’s been used all over the world, in every conceivable situation, and is generally effective at keeping its owner warm and happy. The wetsuit is supreme in its simplicity, bottling in the body heat while still leaving room to layer jackets and other insulation on top. They’re a fairly inexpensive piece of equipment, effective, and don’t restrict your movement in the boat. The wetsuit acts as an evaporation barrier, allowing a thin layer of water to seep in between your skin and the neoprene and trapping it there. That water retains your body heat and, since cold water can’t circulate into its place, adds to the natural insulation properties of the neoprene to keep you warm. That’s all well and good in moderate weather, when the water temperature may be around 50 degrees, but what happens when there’s snow on the ground? When the water goes beyond being just uncomfortable and becomes downright dangerous? Those lightweight, 2-3mm neoprene suits just aren’t going to cut it; you’ll need more insulation.

That’s where the drysuit comes in. These Gore-Tex wonders do more than just keep the heat in; they also keep the water out. Manufacturers like to show off their products by sending paddlers out onto the water in tuxedos and bringing them back bone dry, but the reality is that a drysuit allows you the flexibility to wear whatever insulation you need and stay dry in the process. That means that a well layered drysuit will generally keep you warmer than a similar wetsuit. So why doesn’t everyone wear one? For one thing, they’re expensive. They can run nearly $1,000 new, and the hassle of regular maintenance to keep the rubber gaskets from cracking is too much for some people. If you’re an expedition paddler that needs to handle serious winter conditions, get a drysuit, no question; but for most of us, a good Farmer John wetsuit will do just fine.

Feet

Like most paddlers these days, I like to wear a pair of wet suit booties on my feet whenever I go out on the water. They stay on my feet, give me a good bit of traction in case I swim, and are generally an all-around good idea. As a side benefit, they do a great job of keeping the feet warm by trapping a thin layer of water and holding it against your skin, just like a wetsuit. With the water staying in place, your natural body heat does the rest. They’re not perfect for winter paddling, and they can get a little cold in the boat, but they do the job better than anything else I’ve tried.

Hands

Wet hands are an inevitable part of paddling, and regular knit gloves just can’t handle those kinds of waterlogged conditions. There are two options for cold hands: pogies ¬ neoprene mitts that wrap over your fingers and around the paddle shaft, leaving you skin-on-plastic contact with the paddle (popular with whitewater types because of the extra contact and better touch control); and full neoprene wetsuit gloves that offer more warmth but less “feel.” It’s really up to you which tradeoff you prefer, but pogies have proven a popular option for many paddlers over the years, and are generally warmer than they look.

Head

If there was a fourth universal rule for cold weather paddling, it would be to always wear a hat. Whitewater types, something thin that will fit under your helmet; the rest of us, and warm, synthetic ski cap will do.

Getting to Know Outdoor Fabrics

Polytetrafluoroethylene, “hydrophilic monolithic laminates”, oleophobic or perhaps even WVTRs – enough to make you run to your college bio-chem textbook, right? And you might want to latch onto a dictionary of marketing catch phrase labeling while you are at it.

Sounds like a strange intro to an article on outdoor fabric, doesn’t it? Not so today, especially in a world of hybrid synthetic fibers and micro-layering where products featuring überfabrics and secret proprietary processes with differences measured in microns try to out-perform rivals while vying for the outdoor consumer’s dollar.

Through dozens of years playing on land and on water, I’ve learned about what to wear and not: “There’s no such thing as bad weather – just bad clothing!” was a common landlubber’s warning while “Dress for the water, not for the air” was an oft-repeated safety tip, especially on balmy days when preparing to paddle out onto the frigid waters of the north Pacific. The classic verbal red flag in both environments, however, was: “Cotton Kills!”

So, what is the story about fabrics used for clothing and other gear in our moist, cold and often take-no-prisoners outdoor environment?

BASIC REQUIREMENTS

Our primary, life-sustaining “fabric” is our skin. It’s the body’s largest organ; it protects us from external intrusions as well as helps regulate several internal processes. One very vital process is heat regulation. We need to maintain a core temperature of around 98°F/34°C – you know the numbers. When we get too hot, we start to sweat – our body’s way of helping us cool down. Cool down too much and we become hypothermic – a major killer.

We lose heat through radiation, convection (wind), conduction (cold ground), evaporation and respiration. Moisture against or near your skin (directly or from absorbing layers) can conduct heat away and excessive moisture may not be evaporated or carried away fast enough to prevent core cooling. It can also mask the fact that you are still cooling since sweating is a true indicator: “Hmmm, No sweat! Must no longer be cooling!”

That could be a fatal assumption.

A qualified ideal solution to staying dry and well ventilated in the rain would be to stand naked under a broad umbrella. The dome overhead keeps you dry (heat loss or wind notwithstanding) and your naked body ensures total ventilating of your skin. There are obvious and severe limitations to this particular solution. Hence we have artificial skins in the form of fabrics that attempt to approach that same level of completeness while providing mobility and other obvious benefits.

IN THE BEGINNING – NATURAL FIBERS-

Hemp is probably the oldest fiber known to Man. Akin to wearing burlap, it most likely became a valuable necessity when animal hides were scarce or as easier processing and applications were discovered.

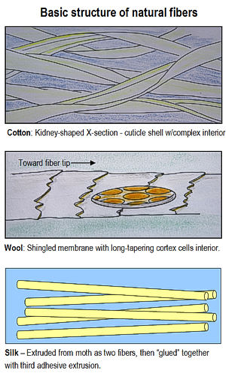

The legend of silk is that a Chinese Emperor’s bride discovered the fiber when a cocoon from a moth fell into her hot tea and unraveled in a long string of thin, but strong strands. The natural process of producing silk involves two extruded fiber sources merging just outside the insect’s mouth and being bonded together by a third extrusion of adhesive. Silk’s strength and softness makes it a fabulous material while it’s great absorption capacity for water (can absorb up to 30% of its weight without feeling wet) adds both pros and cons in certain situations.

Cotton may, indeed “kill” because it absorbs so much water and therefore loses most of its insulating qualities, and also makes the garment incredibly heavy. Cotton is mostly cellulose; the fibers are a complex structure with many electronegative oxygen atoms. These natural bond with electropositive hydrogen atoms in the air. So the oxygen in the cotton and the hydrogen in the water combine (like a water magnet) and – voila- you’ve got some seriously wet cotton! Wearing cotton jeans during a capsize adds many pounds of excess weight and will start cooling you down as soon as you (hopefully!) re-enter your boat. If you don’t recover in time – cotton’s reputation for fatality is validated.

However, it does work well to cool one down as it allows air to flow through the fabric and also protects against UV rays. When combined with certain synthetic fabrics or treatments, many of its negative properties are lessened or mitigated.

Wool is perhaps the best-known and still popular outdoor natural fiber in use today. A close look at a single wool fiber reveals a series of shingle-like overlaps of cuticle cells made up of proteins and waxy lipids forming an outer layer over an inner, cortex core of long-tapering cells. Different wools have different properties of appearance and feel and are used in applications that best utilize those characteristics. One of wool’s most noted features is the fact that it provides warmth even when wet. It’s waxy exterior makes it repel water while allowing vapor to pass through (a term called breathability). These attributes are also primary selling points with most of the synthetic fibers used in outdoor clothing on the market today.

Merino wool, from Australia, is at the acme of the wool fabric world when it comes to its use in outdoor garments. Beyond it’s natural properties of thermal-regulating, moisture-wicking, antimicrobial, insulating, water-repellent, breathable, durable and biodegradable, merino’s fine fibers make it especially soft and comfortable, too. To make this super wool even better, it is blended with a variety of synthetic fibers that combine the attributes of both to make the merino products even stronger, more durable and so on.

THE AGE OF SYNTHETICS

Most modern synthetic fibers are compounds that are combined to form layers that are laminated and made into compounded fabrics. They are most often petro-chemical polymers (from Greek: ,polus=many, much and meros=parts) – a chemical compound or mixture of compounds made up of repeating molecular units. Some synthetics are made from animal or plant bases (rayon is made from cellulose fibers) as well.

The process for forming these fibers is very similar to that used by the moth to make silk. Fiber-forming materials (polymerized petro-chemicals bonded in long molecules joined by adjacent carbon atom) are forced into the air through small openings forming threads. The variety of fibers created share many common characteristics that make them especially suited for outdoor garments including:

- Heat-sensitive

- Resistant to insects, fungi, etc.

- Low moisture absorbency

- Density/specific gravity

- Piling

And because they are usually cheaper to produce and process – economics plays a big role in the outdoor clothing business! One of the most serious drawbacks of synthetic fibers is that while they are usually flame resistant, they will melt. This makes they unsuited for many commercial uses where intense heat may occur – and why you get those melted pits in your fleece and outer shells by sitting downwind of a sparking campfire. Nearly 50% of all fiber use is synthetic with nylon (a thermoplastic – “synthetic silk”), polyester, acrylic and polyolefin making up nearly 98% of that use.

Most of the polymers used in outdoor gear are in the form of films that coat or are laminated to other poly fabric (and sometimes natural ones as well). Let’s look at some of the base synthetics and other materials used alone or compounded in outdoor gear:

Polypropylene films – a thermoplastic polymer resin consisting of branched units derived from propane and joined with methane. It is very similar to polyethylene – the “plastic” in rotomold kayaks!

Polyurethane films – Often listed as “PU” in fabric/application descriptions, it is perhaps the magic ingredient in most waterproof/breathable fabric. It is continually being improved upon and altered as a protective layer on many new fabrics (as it is was initially and still being used as the protecting layer in Gore-Tex™, and other new fabric innovations). PU layers are used to make garments lighter and stretchable, important aspects of fit and comfort in clothing. The are also more impact resistant than other polys (knee areas, hard contact from a fall, etc.).

Polyester films – another polymer but not as performance capable as other “polys” – yet! One advantage it has is that it is recyclable if bonded to another polyester film.

PTFE – Our opening sentence chemical tongue-twister, Polytetrafluoroethylene! It’s a fluorocarbon-based film whose use is widely known as Teflon™. In one of its many hybrid forms it is the definite layer used in the production of Gore-Tex™ and other developing technology entries into the marketplace. The marketing side of outdoor wear has come up with dozens of buzz-words to label their proprietary fabrics, most of which are made from these base polymers using ever-developing attributes, refinements and other secret processes.

Some of the most notable and familiar hybrid fabrics used in clothing and gear include:

- Cordura – We all know the toughness of Cordura (used in clothing and gear, including PFDs and other water products. It offers the durability of nylon with the comfort of cotton: it’s strong, lightweight, highly abrasion resistant, high tensile and tear strengths.

- Neoprene – Easier to say than polychloroprene, it is in a family of synthetic rubbers that are polymers of cholorprene that are ingredients in the production of other materials. When used in diving and insulated garments, the neoprene rubber foamed by impregnating it with nitrogen gas to form tiny, insulating spaces also makes the final garment buoyant. Spandex™ (a polyurethane based co-polymer) whose marketing name is an anagram for “expands” is added to give the neoprene suits even more stretch for fit and comfort.

- “Fleece” – The synthetic kind, is an insulating, soft napped synthetic fabric that is polyethylene or other synthetic fiber based. It has many of the finest wool’s qualities at less weight.

This has been a skeletal overview of the most common base fabrics and fibers used in today’s outdoor garments and gear. The use of these materials in laminates and coats as well as the ever-growing technology on improvements and refinements means a whole new level of clothing options for today’s outdoor enthusiast.

Outdoor Fabrics: Gore-Tex and Beyond

By Tom Watson

“‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves, and the mome raths outgrabe.”

-From the poem “Jabberwocky” by Lewis Carrol

As one enters the realm of petro-chemically-enhanced überfabrics, we begin to pass through a jabberwocky jumble of marketing buzzwords and ultra modern terms for processes and super garments. Each fabric utilizes secret formulas with claims of out performing all competitors on all levels. Some of it is true; some of it is marketing hype – but mostly all have generally raised the bar towards introducing fabric process technology into everyday outdoor wear and gear.

In order to discuss the latest fabrics being used to create paddling clothing and gear, a few more terms need to be defined:

[Read “Part I: Getting to Know Outdoor Fabrics” for previous terms.]

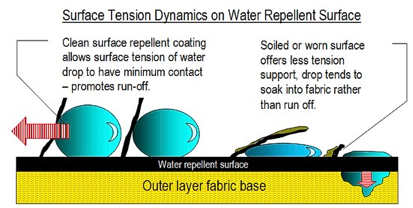

Durable Water Repellent (DWR)

Basically a characteristic that keeps the exterior of the fabric from allowing water to pass down through the surface and into or through any sub layers. DWR materials typically have a surface that uses the water droplet’s surface tension/energy (causes water drops to “bead”) to maintain minimal contact with that outermost layer thereby allowing it to flow off rather than penetrate below. Water repellent applications create or maintain a surface that encourages minimal contact whereas dirt, oils and wear affect the surface area allowing the droplets to spread out and eventually seep through more easily. Fabrics designated as “Waterproof” usually refers to the amount of water under pressure it would take to penetrate a surface.

Breathability (BR)

Probably the most-used buzzword in the clothing industry, its intended use is to describe the process by which water vapor is transported or transmitted through layers of fabric to be dispersed (through evaporation) to the outside or via a vented layer of material. Be advised, there is apparently no standardized lab test to measure “breathability” – it’s more often based on the manufacturer’s own parameters and then promoted according to those findings that support their claims. That doesn’t mean the stuff doesn’t work or perform well – it’s just… marketing! If you see a fabric marked as “WP/BR” it means it’s offered as being both water “proof” and ‘breathable’.

Laminates vs. Coatings

A ‘laminate’ is a layer of material applied to a surface (think wallpaper on a wall). Both Gore-Tex™ and eVent (see below) are laminates where a WP/BR membrane is bonded to a sub layer. A coating is usually a WP/BR polyurethane resin solution that is applied directly onto the fibers. Some of the new processes boast better utility by infusing the WP/BR properties into the fibers rather than merely covering the surface like a thin coat of paint.

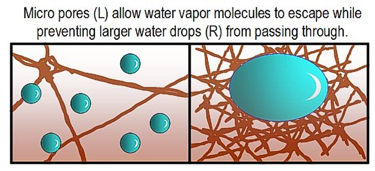

Coatings can be subdivided:

Microporous coatings are composed of microscopically small channels that are created in the coating by adding a foaming agent that creates gas bubbles – they expand within the coating to form passages large enough to allow water vapor through so the coating can “breathe”. Monolithic coatings enable water-attracting fibers to facilitate the movement of moisture through the fabric.

Two other terms that appear often when discussing the attributes of a fabric are hydrophobic – usually continuous pores that allow water vapor to pass through, (a water droplet is too large to pass through whereas the water vapor molecule is much smaller than the passageway); and hydrophilic – a solid membrane that enables water at a molecular level to move through the membrane via solid state diffusion (this has been likened to someone moving along a monkey bars in a playground).

So what does all this have to do with paddling clothing? Well, it’s all about how our body’s heat loss/retention and hydration processes function. If we get too wet from the cooling effects of sweat, we can both dehydrate and chill down to dangerous levels approaching hypothermia. Getting rid of that excess moisture is dependent on how effectively that water is transferred to the outside via WP/BR materials or simple ventilation. Add to that our individual comfort zones when participating in the outdoor environment, we have several factors to consider when using the right clothing and gear.

One of the factors in all this is humans – we are all different, we react to the same environments differently due to activity levels, physique and metabolism. We need to enable excess moisture to be removed from next to our skin, that moisture needs to escape so our mid layers don’t get soaked and ultimately so we don’t suffer from too great a loss in body temperature – and we need to find a piece of apparel that will provide all those benefits based on our particular body/activity type…and budget, style preferences, etc.

So, we have the natural fibers that are often combined with synthetics to mutually enhance the performance of each. We have specialized fabrics such as fleece and neoprene that provide insulating layering options and we have the newest fabrics (many under fancy names that are all based on the same foundations with their own “secret” process added).

Raising the bar

The best thing about early forms of Gore-Tex was that it drew attention to this whole world of breathability and waterproofness and what not. Sure it had problems when it was soiled and didn’t always keep you completely dry as you may have presumed. Patented in 1976 it quickly became the miracle fabric, the gold standard of the outdoor industry.

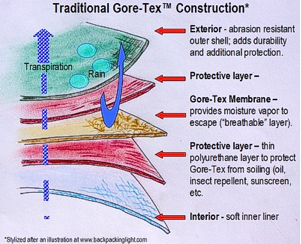

Gore-Tex is a basically a porous, monolithic/hydrophilic membrane of a polymer with the same constituency of Teflon™ (a PTFE as defined in Part I). Its structure is that of a series of microscopic nodes attached to fibrils. It is most often applied as an inner layer between protective outer and innermost layers.

- FACTOIDS:

- Gore-Tex has nearly 10 billion pores/square inch

- Each pore is 1/20,000th the size of a water drop

- A water molecule is 700 times smaller than a pore opening.

Gore-Tex’s key attribute is that of being “waterproof”; it enables water to pass through the material through the process of diffusion. One criticism of its function is that the wearer needs to be producing quite a bit of moisture before the fabric “kicks in” and starts diffusing. Also, Gore-Tex uses a PU layer to protect the Gore-Tex from dirt, oil and other pore cloggers. In 2010, Gore introduced Active Shell as an improvement over conventional Gore-Tex. The new process incorporates a no-glue bond to a thinner PU layer that still works on the diffusion principle of water transfer.

Enter eVent, one of a few new fabric/processes on the market that is claiming new standards for outdoor waterproof and air permeable. Instead of using a protective PU layer to block against oil, dirt, etc., eVent found a way to incorporate that characteristic directly into/onto their PTFE layer.

Other entries in the competition with traditional “breathables” include Polartec Neo Shell claiming to be the most breathable fabric on the market, citing five times the air permeability rates of Gore-Tex and eVent. Apparently part of Polartec’s secret technology is that the membrane is not even PTFE, it’s PU! Another serious contender is Entrant by Toray. Its claims of breathability put it between Gore-Tex and eVent.

NRS, Columbia, REI and many other purveyors of outdoor apparel feature advanced technology fabrics in their products – each offering their own range of lab stats and benefits. In general, PTFE is more durable than PU, which is why laminates or processes are added as enhancements to offset certain limitations in companion layers.

Rather than go into claims about each new miracle überfabric soon-to-be or currently introduced, know that each manufacturer makes boasts and comparisons of superior features that include secret processes and proprietary lab tests which seem to always show their product coming out on top. Truth seems to be that they are all pretty darn good. Factors of pricing, durability, weight, comfort all affect what process or fabric is available for any particular piece of clothing.

PERFORMANCE UPKEEP

Like other outdoor equipment, clothing is gear; it needs to be maintained for function and safety. These new fabrics aren’t Superman’s cape, they do suffer from use and abuse. There are some basic maintenance procedures you should follow to optimize the usefulness and life of your garment. Most will have cleaning instructions but general rules are:

• Use regular liquid laundry detergents in warm water, rinse twice

• Do not use fabric softeners or bleach

• Do not dry clean

• Some can be ironed but on “warm” setting, and very carefully

• If water fails to bead, consider applying a surface water repellent

Bottom line?

On-water fabric/material for clothing is pretty much use-specific (neoprene for wetsuits and booties, nylons for simple splash jackets, cordura for PFDs, etc.). Higher end paddling gear gets into these super fabrics in limited styles. Once ashore, however, especially once one becomes engaged in other companion activities a change of wardrobe is often in order. That’s where these fabric options can open up the field for paddlers.

No matter which specialty fabric you decide upon, it’s still proper layering and venting (very important regardless of what super clothing you choose) that will play very important roles in the optimum functioning of that apparel. In many cases a simple waterproof splash jacket or raincoat can work nearly as well with proper ventilation (encouraged by vents, zippers, fit).

The best testing ground will be actual use in the field within your normal activity level in any given environment. Of course, one person’s sweat lodge is another’s ice box so check around – try to base you choices on practical field use experiences and peer opinions, not just biased lab tests and jabber-hype. Seek out your own comfort/function/utility zone when it comes to choosing your paddling apparel.

Developed 2014